How to improve Kentucky's low labor force participation rate and why changes to UI benefits are not the answer

Given the tight labor market we are currently experiencing, the labor force participation rate is receiving a lot of attention. The labor force participation rate measures the percentage of all people age 16 and over who are either working or actively looking for work. It is the sum of employed and unemployed workers divided by all people legally eligible to work (you can watch our video explaining the labor force participation rate here).

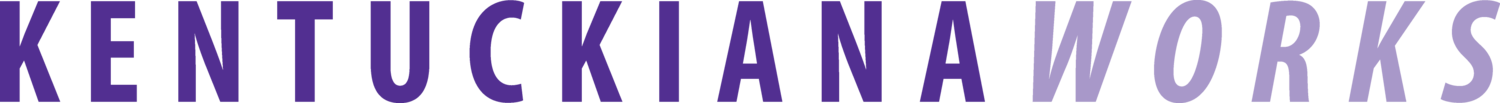

Kentucky’s labor force participation rate has historically been lower than the nation’s rate. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state’s labor force participation rate fell significantly. It has been increasing in recent months, but is still below its pre-pandemic level. As of January, the state’s labor force participation rate was 58%, the 7th lowest among states.

There are many reasons for Kentucky’s low workforce participation rate. Therefore, it is likely to take a number of different strategies and policies to address. Recently, Kentucky legislators made changes to the unemployment insurance (UI) benefit program to address the low labor force participation in the state. On Monday, the Kentucky General Assembly overrode Governor Beshear’s veto of House Bill 4, which will limit the number of weeks individuals can receive UI benefits and increase required job search efforts.

It is critical to point out that individuals receiving UI benefits are by definition already in the labor force. So, any individual who is out of work, but actively looking for a job – a requirement to receive UI benefits – is already counted in the labor force. It is incorrect to claim that changes to UI eligibility will have any significant change on the state’s labor force participation rate.

Unemployment insurance benefits are available to individuals who have lost their job through no fault of their own, not to individuals who voluntarily quit, retire, or are otherwise not employed. Under the current UI program, individuals can receive up to 26 weeks of payments for a percentage of their previous wages. The intent of the program is to provide a cushion while they seek other employment.

“It is critical to point out that individuals receiving UI benefits are by definition already in the labor force. So, any individual who is out of work, but actively looking for a job – a requirement to receive UI benefits – is already counted in the labor force.”

Access to UI benefits are an important resource to laid off workers. They provide some financial stability in an otherwise stressful time period. With the resources to keep a roof over their head and food on the table, laid off workers can spend time finding another job that makes good use of their skills and talent. Research shows that access to UI benefits results in better matches between workers and available jobs, which in turn increases productivity. This is good for the individual worker, businesses, and the overall economy.

UI benefits support the overall economy in another important way. Because more people lose their job during economic downturns, access to these supplemental funds helps to limit the severity of the recession. Rather than cutting off all cash flow from workers who lost their jobs, UI benefits enable them to keep some money circulating in the economy.

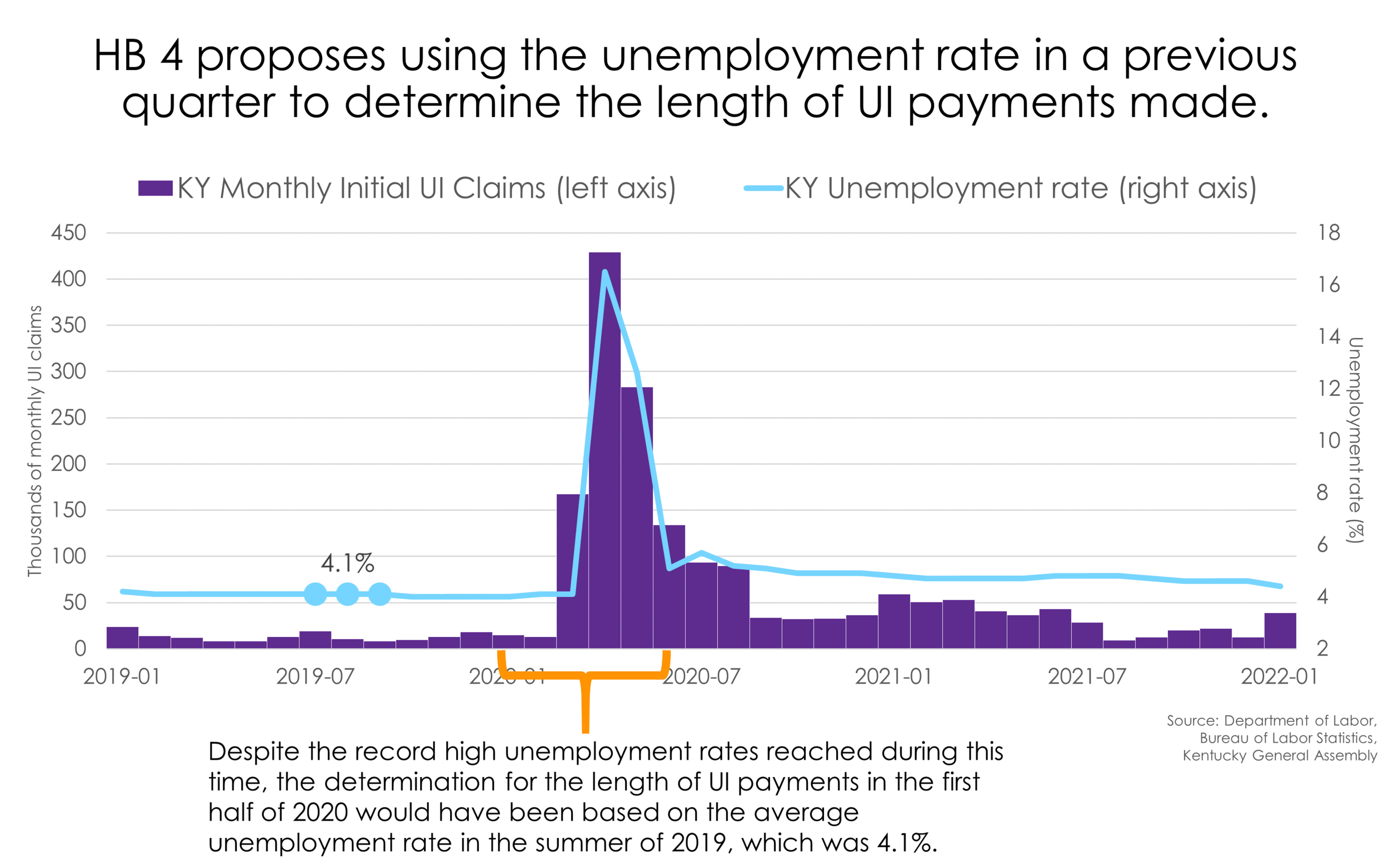

The proposed changes to UI benefits in House Bill 4 make the program less responsive to economic downturns. The length of time laid off workers will be able to access UI payments is based on the unemployment rate in an earlier quarter, a process referred to as “indexing.” It is easiest to understand the implications of the policy in the future by looking at how the proposed policy would have played out in the past. For example, if this policy had been in place in 2020, UI claims made from January 2020 through June 2020 would have been limited to 12 weeks. Despite the record high unemployment rates reached during this time, the determination for the length of UI payments would have been based on the average unemployment rate in the summer of 2019, when the economy was not in a recession. Similarly, if this policy had been in place in 2008, UI claims made from January 2008 through June 2008 would have been limited to 13 weeks because the determination for the length of UI payments would have been based on the unemployment rate in the summer of 2007, when the economy was not in a recession. UI payments for those who lost their job at the very beginning of the Great Recession would have ended by October 2008, nearly a year before the recession was over.

Economic downturns are unpredictable. It is difficult to know when they will start or when they will end. But we can expect that the unemployment rate will increase during a recession, and with that, the number of people accessing UI benefits. If those laid off workers are not able to access their benefits for very long, and the recession drags on with a low rate of job openings (as it did during the Great Recession), it will become difficult to cover the costs of basic needs. This can exacerbate the length of the recession by reducing consumer spending, leading to additional layoffs and UI claims, in addition to creating financial hardship for individuals and their families.

If the target is to increase the state’s workforce participation rate, then changing the UI benefits program is unlikely to achieve this goal. Addressing the reasons people are not working, and not actively looking for work, are the mechanisms for improving the state’s low labor force participation.

It is important to remember there are perfectly valid reasons to drop out of the labor force. Since the workforce participation rate reflects all people age 16 and over, it shouldn’t be too surprising that nearly 60% of individuals not participating in the labor force are either retired or in school. The number of retirees has been increasing in recent years as the Baby Boomer generation ages. Research shows that the rate of retirements during the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated, as the stock market boomed and the virus spread. One way to address the state’s low labor force participation rate would be aimed at keeping older workers in the workforce longer, by offering flexible schedules and phased retirement programs.

Another trend of recent years is the number of Kentuckians citing care responsibilities as the reason they are not in the workforce. Throughout 2021 an average of more than 200,000 Kentuckians – 1 in 7 of those out of the workforce – cited taking care of family and home as the reason they were not in the labor force. Policies aimed at improving access to affordable, reliable child care would help reverse this trend.

Although declining in recent years, the number of Kentuckians citing disability or illness as preventing them from participating in the labor force still accounts for nearly a quarter of those out of the workforce, a rate nine percentage points higher than the nation. Policies aimed at improving economic opportunity for disabled individuals would have a dramatic impact on the state’s workforce participation.

Only 3% of Kentuckians cite another reason for not participating in the labor force. Therefore, policies targeting child care and economic opportunity for individuals with a disability and older workers are the main instruments for improving the state’s labor force participation rate.