The role of child care in the labor force participation rate among women

As the economy continues to recover from the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, the labor market has become increasingly tight. There are currently two job openings for every unemployed person in the U.S. But what about those not counted in the unemployment rate because they have dropped out of the labor force altogether?

I previously covered research on the labor force participation rate in Kentucky (here and here). During the so-called “she-cession” of the pandemic recession, the role of child care in enabling prime-age workers, particularly women, to participate in the labor force has received notable attention.

Research shows that mothers of young children accounted for nearly a quarter of the unanticipated employment loss related to COVID-19. In Kentucky, more than 200,000 individuals cited taking care of family and home as the primary reason they did not participate in the labor force last year.

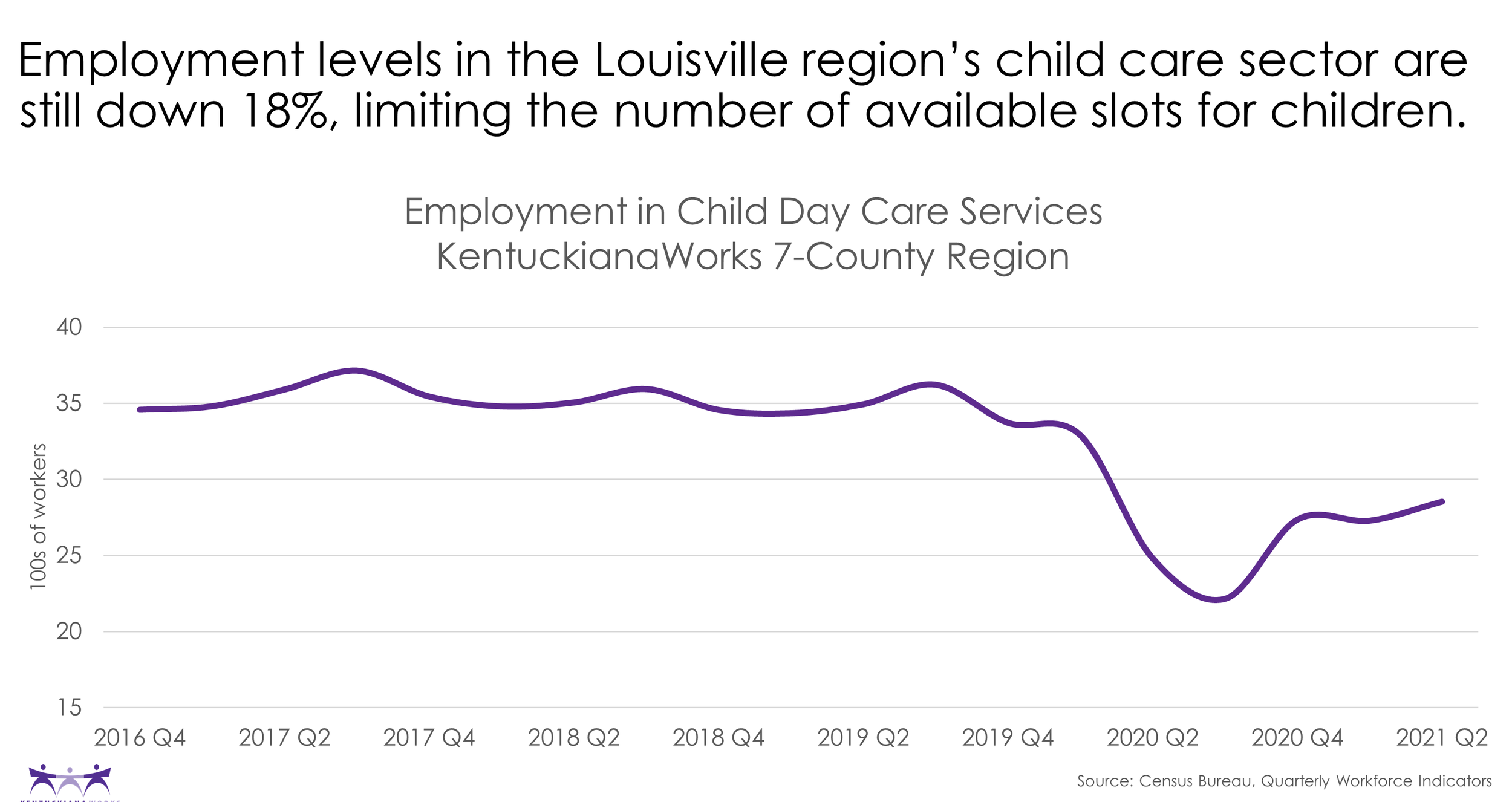

Access to affordable, reliable child care was a challenge before the pandemic, and has only gotten worse since. In the 7-county Louisville region, employment levels in the child care industry are still down 18% compared to their pre-pandemic levels, while employment across all industries is only down 6%.

Lower employment levels in the child care sector directly impact both the availability and affordability of child care to the region’s parents. For good reason, the child care industry is regulated to ensure adequate staffing ratios to the number of children under their care. As employment levels decrease, then so too does the number of available slots for children.

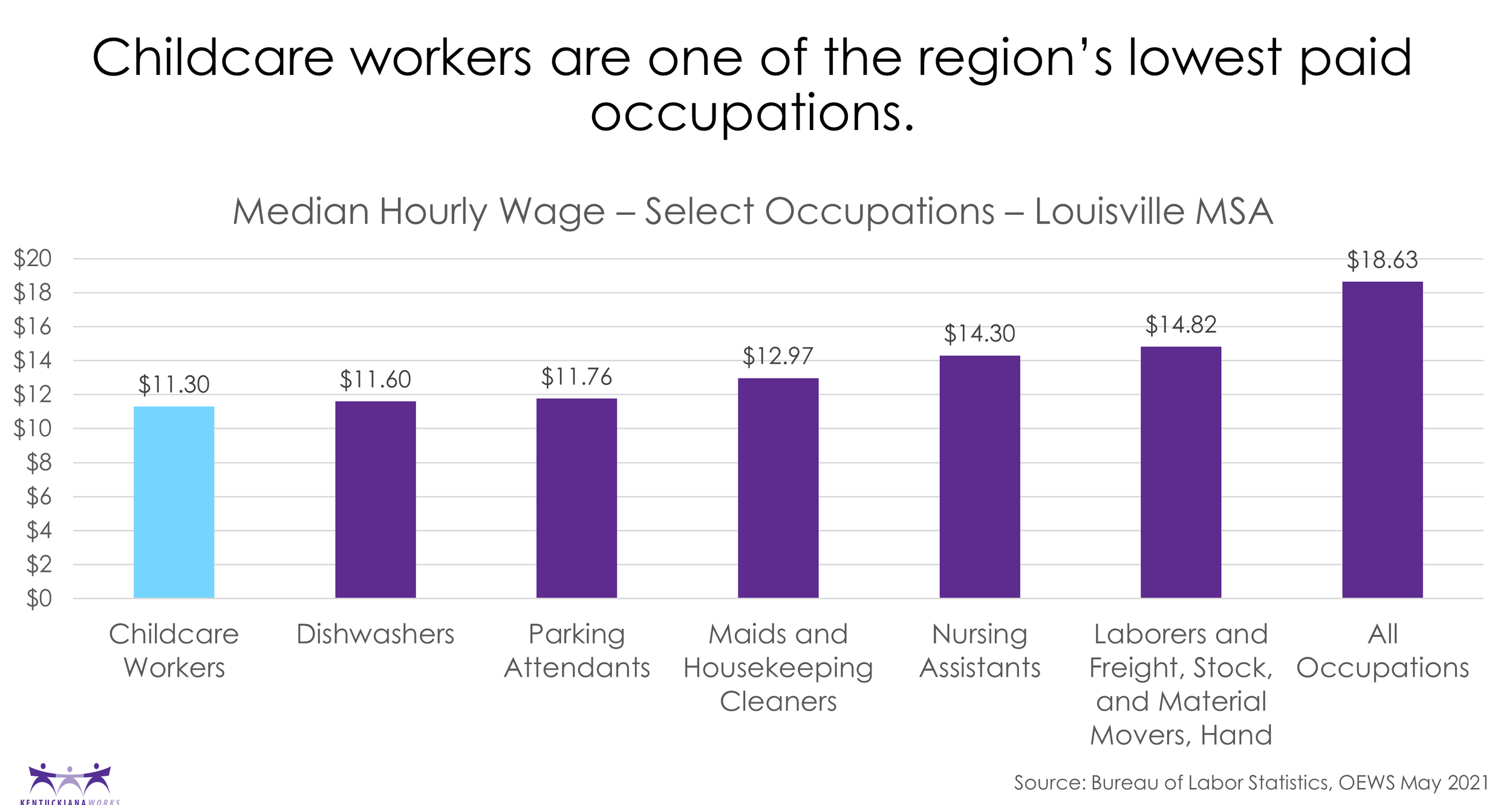

It is not entirely surprising that employment levels have not rebounded in the child care industry. Wages are significantly lower for child care workers than all workers, as it is the 12th lowest paid occupation in the region based on median hourly wage. Low wages coupled with COVID risks from interacting with a population who are not eligible for vaccines can make this occupation particularly unattractive, especially as other low-wage jobs have experienced significant wage increases.

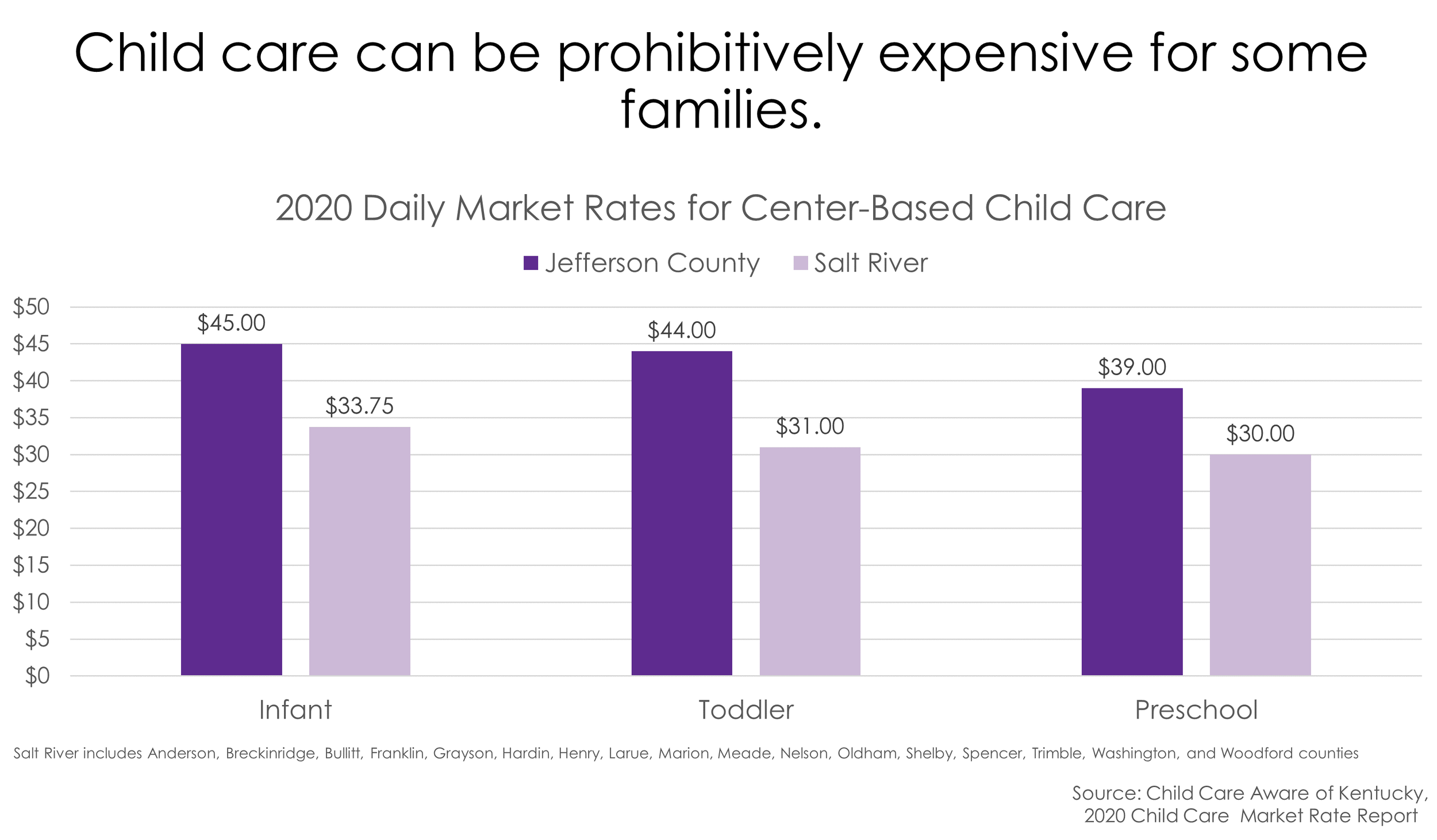

Child care centers operate on very thin margins which makes increasing wages to compete with other sectors difficult. But in order to attract and keep workers, child care centers have been increasing wages, even if not at the rate of other sectors in this tight labor market. These costs are immediately passed on to parents. Indeed, research shows that the cost of child care has been rising much faster than overall prices.

The 2020 Child Care Market Rate report for Kentucky shows that the daily cost of infant care in a center-based facility in Jefferson County was $45 per day. For full-time, year-round care, this amounts to $11,700 per year, 20% of Louisville’s median household income. While infant-care is the most expensive, there are not significant savings as young children age. The same care for toddlers is $44 per day, and $39 per day for preschool aged children ($11,440 and $10,140 per year, respectively). These costs can make child care prohibitively expensive for some families, driving parents out of the labor force.

The low-wage-work/high-cost-service conundrum of the child care sector is driven by how labor intensive the work is. While these safeguards are in place for good reasons, the sector has been deemed by the Treasury Department as a market failure, wherein the private sector cannot provide the optimal solution on its own. This implies a need for public sector support, and given the impact to businesses in need of a labor supply, also suggests a role for employers to step in.

Investments in child care reap many rewards down the line. Not only are workforce participation rates improved, but the children themselves benefit from high quality child care. Research shows important social and economic benefits from high quality child care, which produces a significant ROI.

Kentucky lawmakers recently passed House Bill 499, which provides a state matching fund for child care when employers offer stipends to help cover the costs of child care. The nature of the matching funds requires the business community to step up in offering child care subsidies to its workers, which will then be matched by the state. If used effectively, this could be a substantial improvement in making child care affordable for many low-income Kentuckians.