Who are the adults in their prime working years who are not working?

The United States is currently experiencing the largest economic expansion in its history, along with record low unemployment rates. In such a tight labor market, employers are having difficulty filling their open positions. More attention is now being placed on the population who is not working, and how they could be connected to employers with hiring needs. In this article, we take a look at the adults in the Louisville region who are not working, and the potential barriers they face in seeking, gaining, and retaining employment.

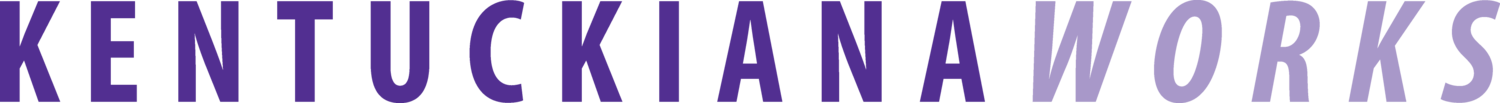

The Louisville metropolitan area is enjoying the nation’s good economic conditions. The unemployment rate in the Louisville region stands at an 18-year low, and total employment is higher than it has been since at least 1990.

However, the unemployment rate only reflects those who are actively seeking a job, and so may not fully describe the entire picture of the labor market. Among Louisville’s population who are eligible to work, one-third are not seeking employment.

Certain segments of the population are not as likely to be seeking work. Young adults, ages 16 to 24, are more likely to be enrolled in school and choose not to participate in the labor force. Similarly, older adults, over age 55, are at or near retirement age and choose not to participate in the labor force. So rather than look at the entire population who are eligible to work, it is helpful to focus on prime working age adults, those between the ages of 25 and 54. Adults in this age range are likely to have completed school and are not approaching retirement age, making them the most likely to participate in the labor force. Of prime working age adults in the Louisville region, 15% are not seeking work.

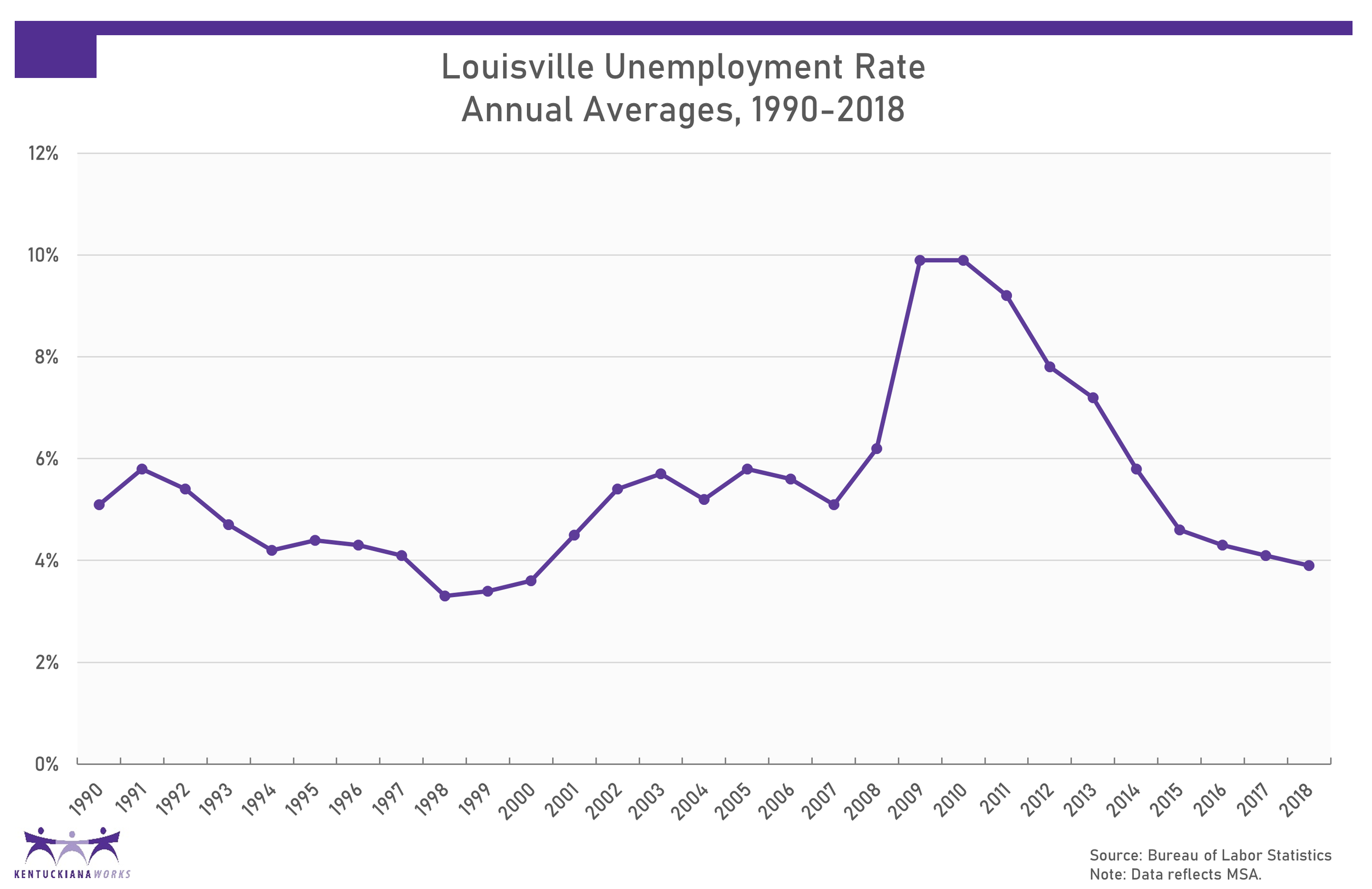

Employers are looking for workers to fill their available jobs. In the second quarter of 2019, there were 43,000 online job postings in the Louisville area. At the same time, there are 20,000 prime working age adults who are seeking work, but not currently employed. In addition, there are 75,000 prime working age adults who are not seeking work. This amounts to 95,000 prime working age adults who are not working in the Louisville area, nearly 20% of the region’s prime working age adults, and more than enough to fill the available jobs of local employers. Who are the prime working age adults who are not working? What are the potential barriers they face in seeking, gaining, and retaining employment?

Characteristics of Adults in their Prime Working Years who are Not Working

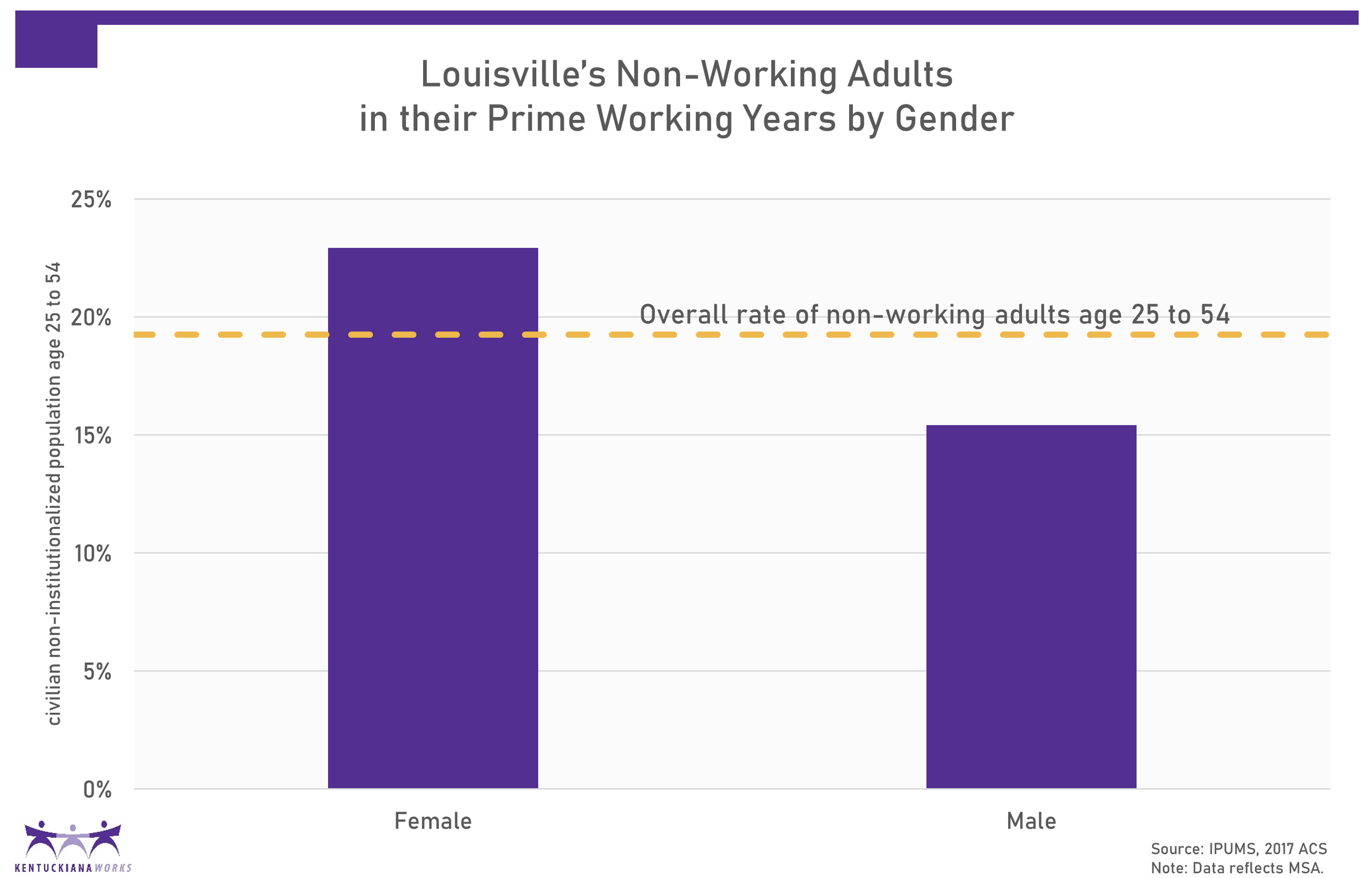

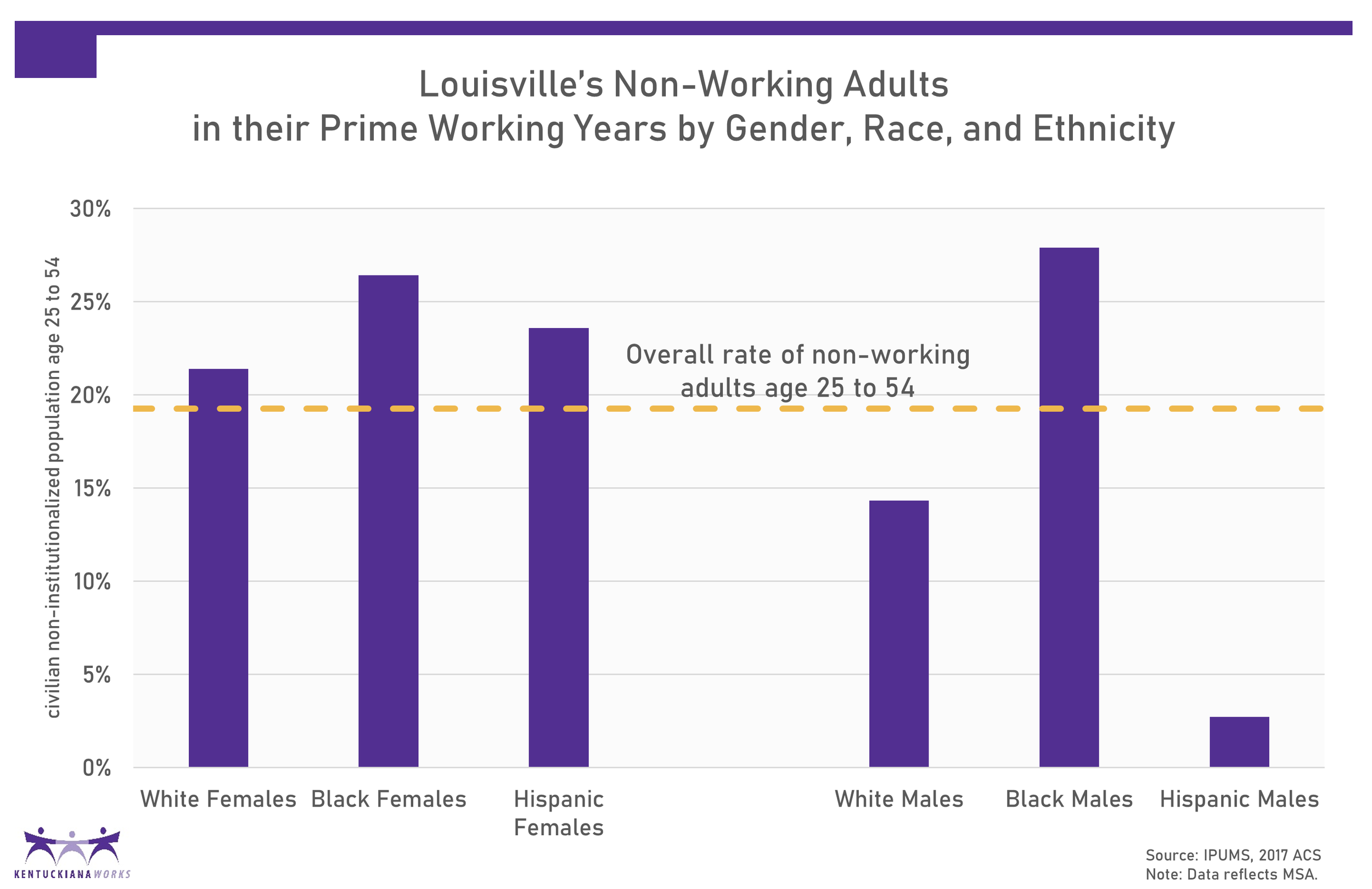

Compared to the overall rate of non-working adults in their prime working years, women have a higher rate of prime working age adults that are not working, while the rate among men in their prime working years is lower.

Women in their prime working years have a higher rate of non-working adults across racial groups. Among prime working age males, only Black men have a higher rate of non-working adults, while White and Hispanic men are more likely to be working.

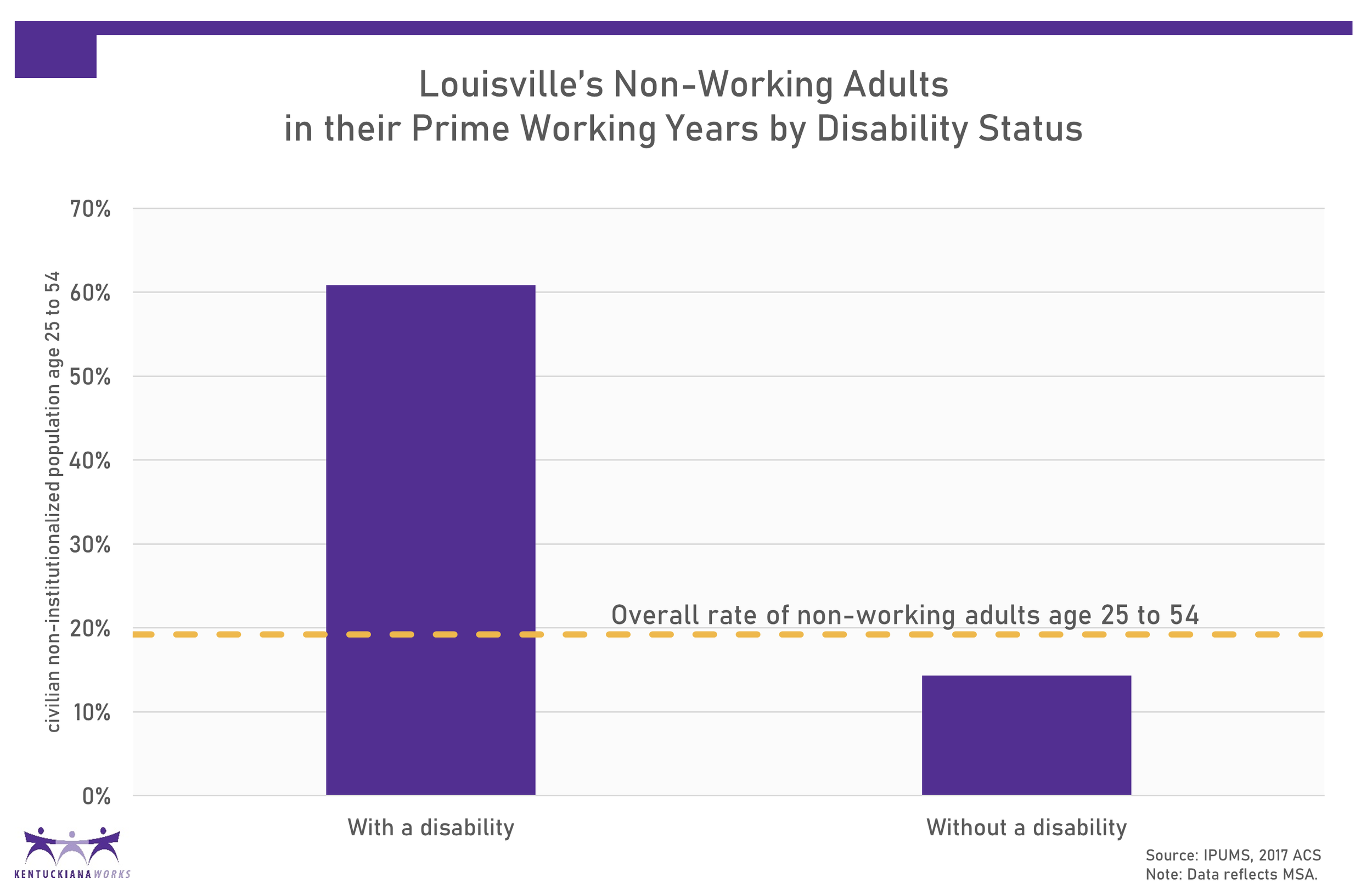

Having a disability greatly increases the likelihood that a prime working age adult is not working. 60% of adults of age 25 to 54 with a disability are not working, triple the overall rate.

Educational attainment is another strong predictor of whether a prime working age adult is employed. Adults without a high school degree or GED have the highest rate of non-working prime age adults, double the overall rate. Adults with only a high school education also have an above average rate of not working. Prime working age adults with higher levels of education attainment are more likely to be employed.

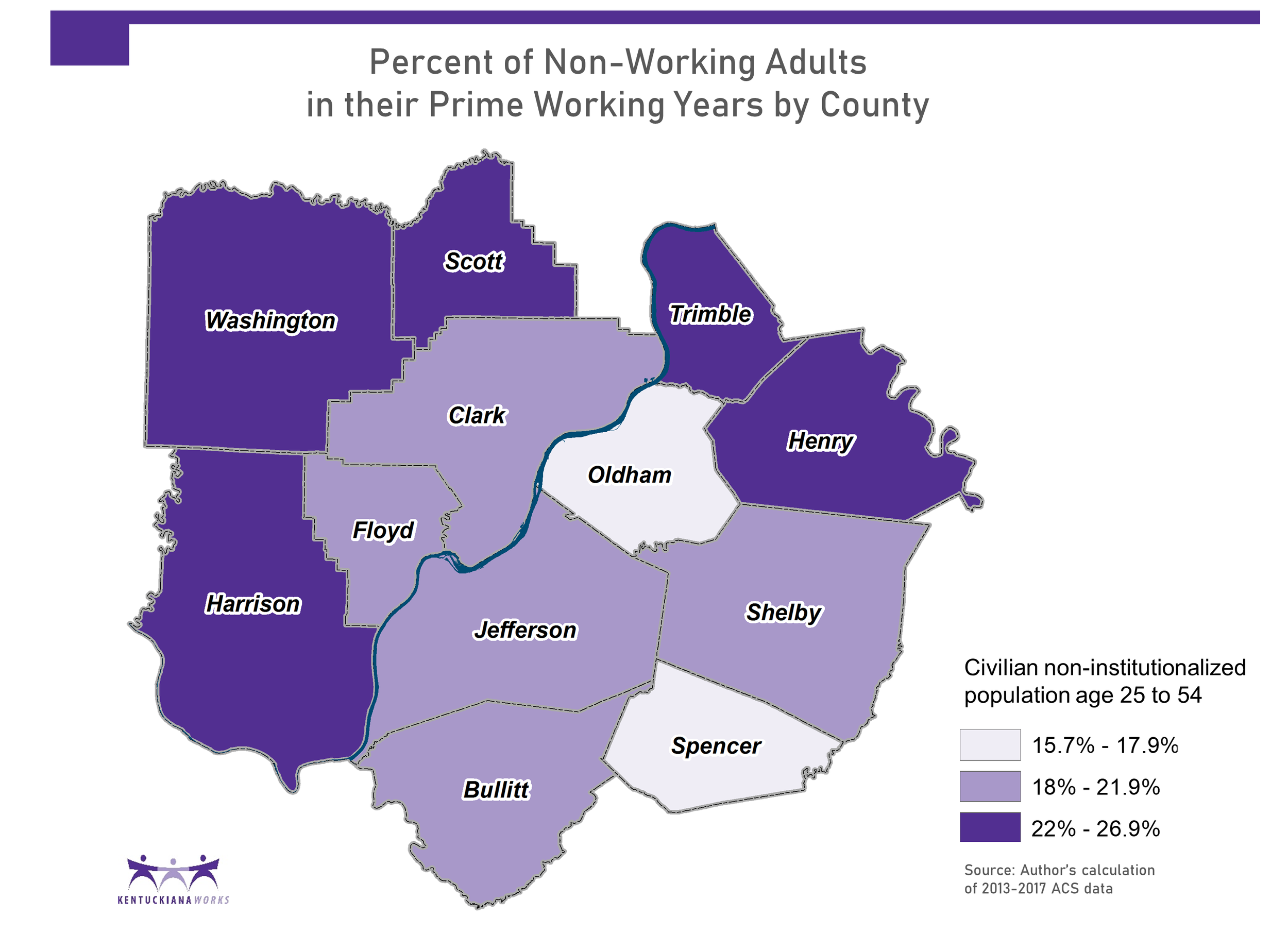

The distribution of prime working age adults who are not working varies across the metropolitan area. The furthest outlying, rural counties have the highest percentage of non-working adults age 25 to 54. Oldham and Spencer counties have the lowest rate of non-working adults in their prime working years.

There is also variation within counties among employment status for adults in their prime working years. Within Jefferson County, adults in their prime working years are more likely to be working if they live east of I-65, and less likely to be working if they live west of I-65. There are also significant pockets of non-working adults in their prime working years in the outlying counties of the metropolitan area.

Barriers to Employment

We do not have good survey data at the local level on the individual reasons why adults in their prime working years are not working. However there are well-understood barriers to employment, such that federal funding administered through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act can be dispersed to help mitigate these challenges. Issues such as the affordability and availability of childcare, court-involvement, reliable transportation, and sufficient education and training can have a big impact on whether a prime working age adult is employed.

Affordability and Availability of Child Care

While some women of prime working age may be making a deliberate choice to not work in order to take care of family, others may be limited in their options while balancing work and family. MIT estimates the local price for the lowest cost child care option for one child at $6,280 per year. Consider a single mother who is seeking to re-enter the labor force. She recently found a job opportunity as a receptionist paying $14 per hour. The position is full-time, so she can earn about $29,000 per year, but she will need to put her young son in child care. However, this rate of pay is slightly too high for her to be eligible for child care assistance in Kentucky. If she takes the job, she will spend 20% of her income on child care alone, making it difficult to cover the costs of other essentials such as housing, healthcare, food, and transportation. Indeed, the Department of Health and Human Services recommends a working family spend no more than 7% of their income on child care. By those standards, a working family would need to earn nearly $90,000 per year for affordable child care costs for one child. MIT estimates the earnings required for a single parent with one child to just make ends meet at $48,000 per year (or $23 per hour). Two-thirds of the region’s jobs are in occupations with a median wage below this threshold.

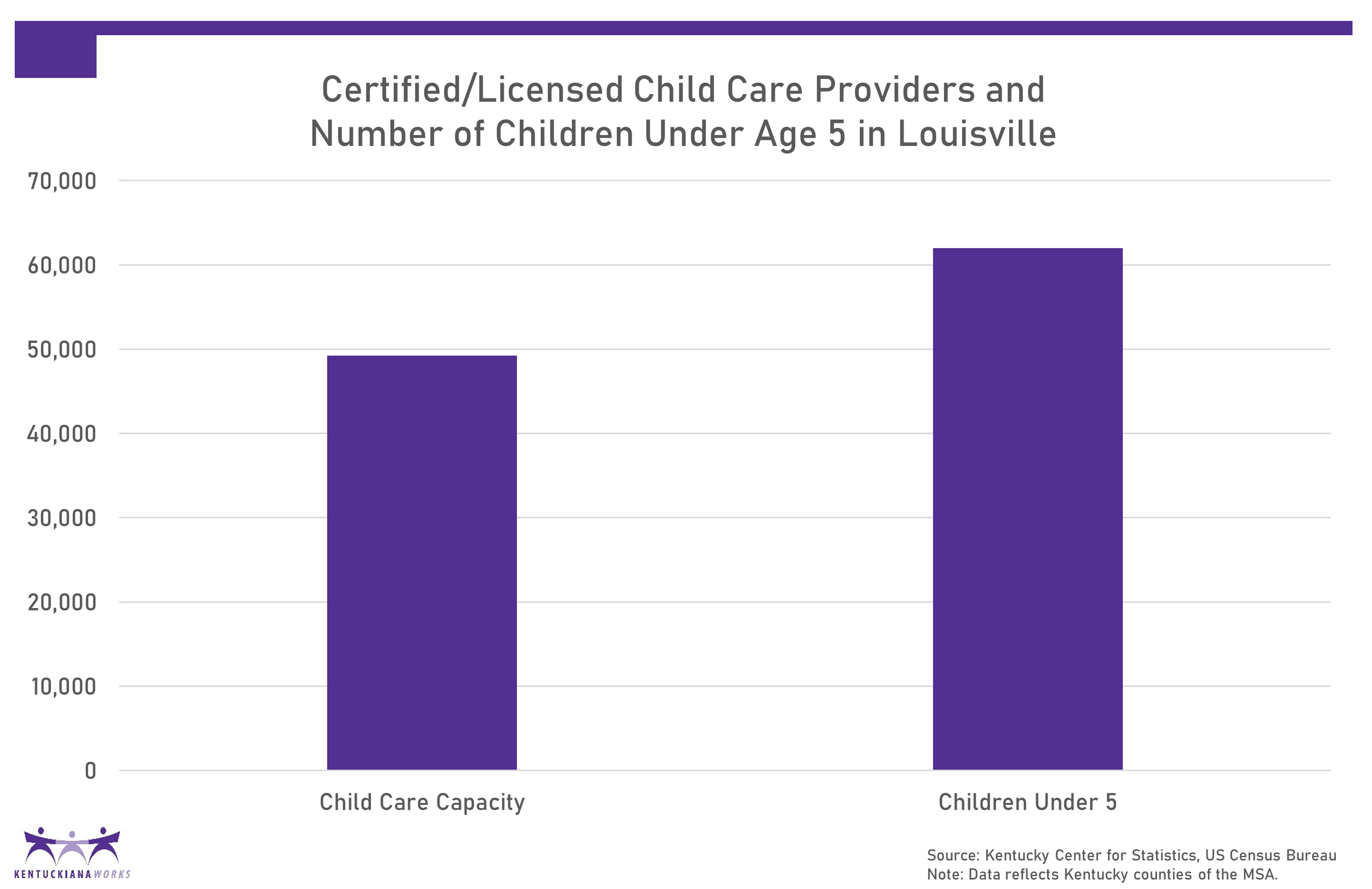

The availability of child care is another consideration working families have to take into account. Within the Kentucky counties of the Louisville metropolitan area, there are a greater number of children under five than there are available slots in certified or licensed child care facilities in the same counties.

The availability of child care facilities varies across the region. Only Oldham County has sufficient child care capacity for the number of children under 5 living there. In Trimble County, there are seven children for every one slot in a child care facility.

Criminal Justice Involvement

Among men, Black men are the only racial group less likely to be working. One contributing factor for this pattern may be the disproportionate rate at which Black individuals are incarcerated. While currently incarcerated individuals are not reflected in this analysis (because they are not eligible to work), formerly incarcerated individuals face additional barriers when seeking work.

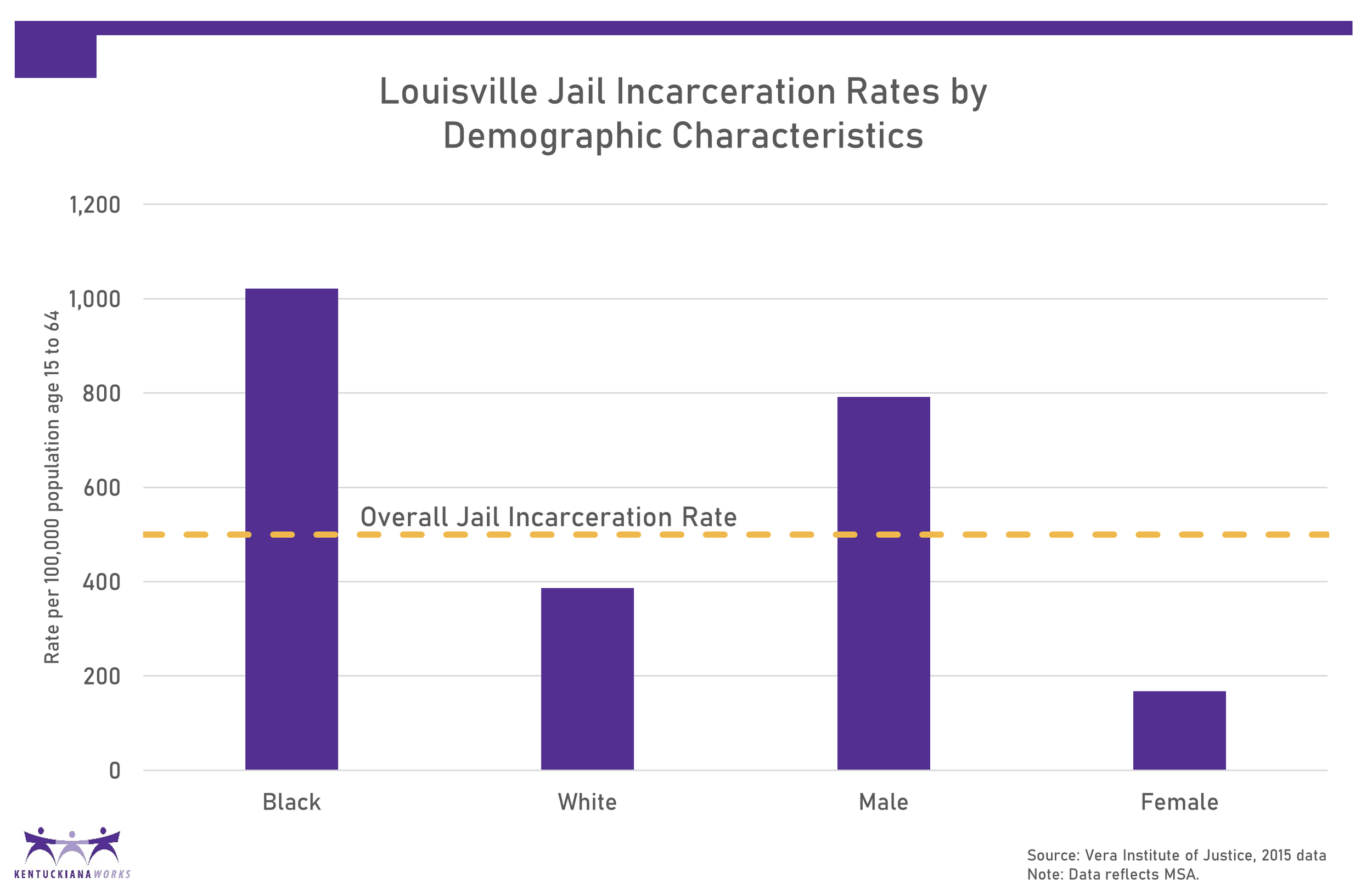

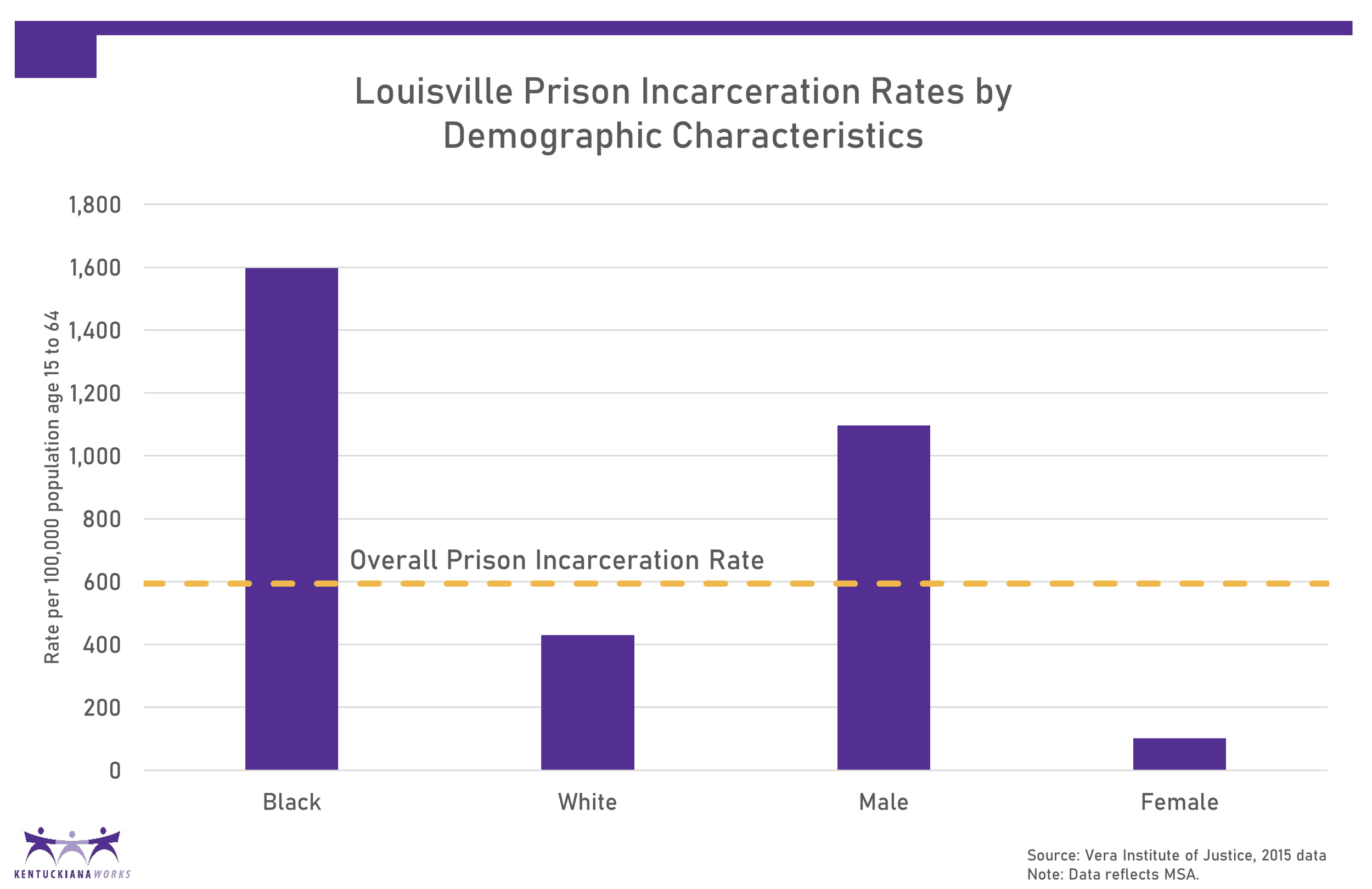

Black individuals and men experience incarceration rates at a much higher rate than other demographic groups, and are therefore more likely to confront the labor market with a record of court involvement.

Incarceration rates vary across the region. The ZIP codes with the highest incarceration rates are concentrated in northwest Jefferson County. Pockets of central Jefferson County, southern Bullitt County, and Scott County also have ZIP codes with higher incarceration rates.

Adults who have been justice-involved have limited employment options, as positions in healthcare, financial institutions, and education are often off limits to someone with a criminal background. Even if a position is not outright prohibited, employers are often times less likely to hire someone who was previously incarcerated. In the first full calendar year after release, almost half of former prisoners do not have any reported earnings. Those who do find employment tend to be in low-wage work, with median earnings of just over $10,000 a year.

Decentralized Employment Centers and Commute Times

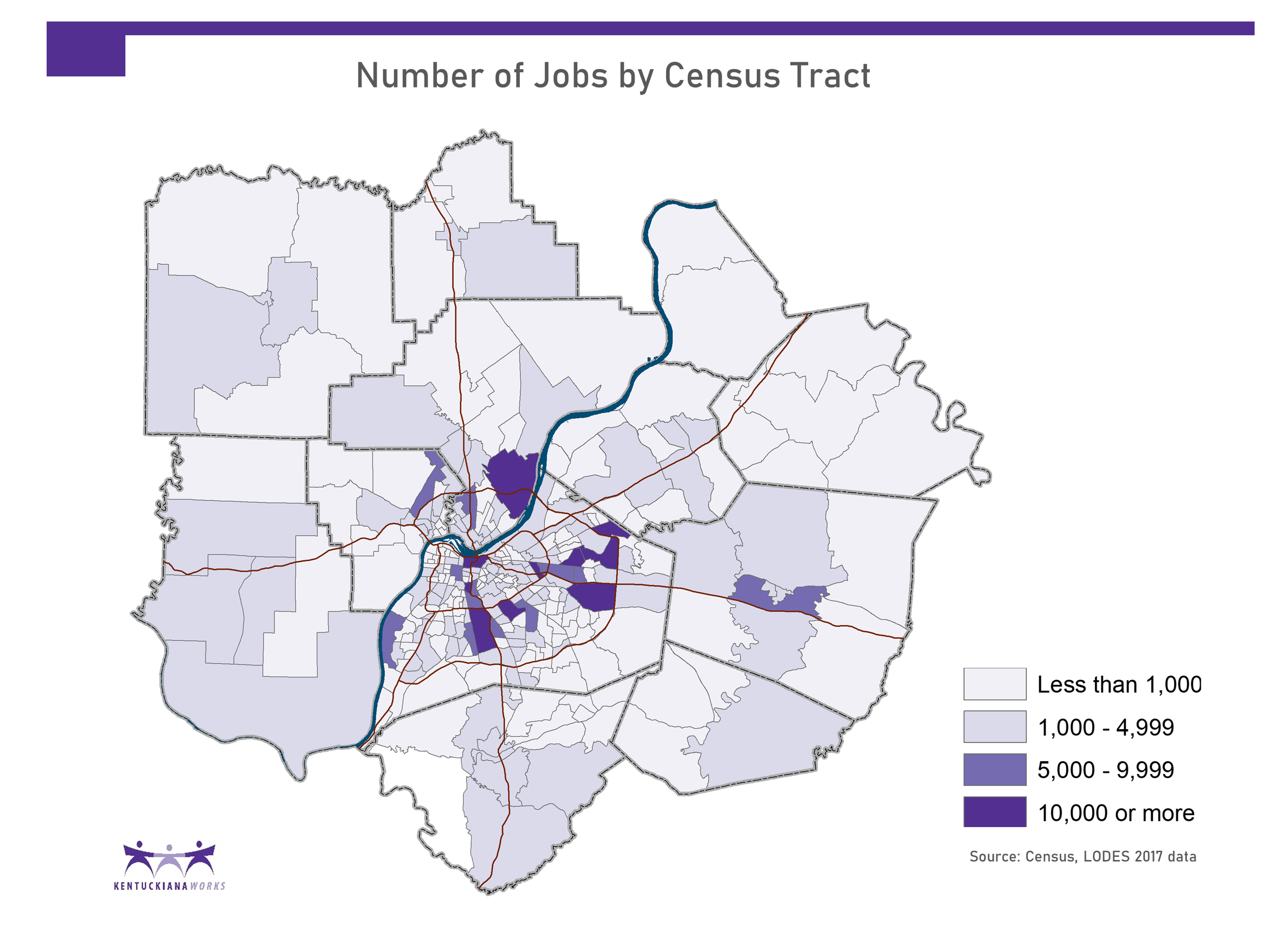

Employment centers within the Louisville region are not highly centralized. While downtown remains the largest employment center, fifteen out of the twenty census tracts with the most jobs are located outside of the Watterson Expressway.

TARC has accommodated sprawling job centers and residential development, spreading its limited resources over a larger geographic area to help connect workers with employment centers.

However, Louisville workers relying on public transportation face longer commute times. While over two-thirds of commuters who drive alone to work have a commute time of less than 30 minutes, the opposite is true for commuters using public transportation. Two-thirds of transit commutes are 30 minutes or more. More than a quarter of workers using public transportation have a one-way commute of at least an hour. For individuals balancing child care, working non-standard shifts, or facing inconsistent scheduling, relying on public transportation may not be a feasible option. Those who do commit to long commutes are more likely to suffer from poor health outcomes, which can also impact work performance.

Job Composition

Since 2001, the fastest growing jobs in the Louisville region are those that typically require at least a Bachelor’s degree. The slowest growing jobs have been those that typically require only a high school education or less. As more jobs demand higher levels of education, those with lower educational attainment may find themselves unqualified for the types of jobs available.

Conclusion

The programming offered through KentuckianaWorks seeks to help address these challenges. Training programs available in manufacturing, construction, and IT help people gain valuable skillsets sought by employers. Project CASE provides work experiences and job placement for individuals with disabilities. Supportive service funds are available for individuals who need help with child care and transportation. But federal investments in employment and job training services have been declining, limiting the reach of these resources. Considering the scope of some of the issues raised here, and in light of a fiscally constrained workforce system, broad-based solutions are needed. As Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve noted in his August speech in Jackson Hole, employer practices can have a big impact in alleviating some of these barriers to employment.

“We increasingly hear reports that employers are training workers who lack required skills, adapting jobs to the needs of employees with family responsibilities, and offering second chances to people who need one.

”

Within our current positive economic conditions, employers have an opportunity to attract populations they might not otherwise engage with by considering how their practices help or hamper individuals who are not working and the associated challenges they might be navigating.