One-in-ten Louisville Young Adults Disconnected from the Labor Market

For many young people, the transition into adulthood has become a lengthier and more complicated process than it was in the past. Opportunities within the labor market for those without a high-school education have all but evaporated, while the cost of obtaining a college degree has skyrocketed. Employers have been trending towards a preference for job experience for even entry-level jobs, limiting what jobs young people can apply for. These hurdles have made engaging with the workforce an increasingly difficult proposition even for the most prepared young people.

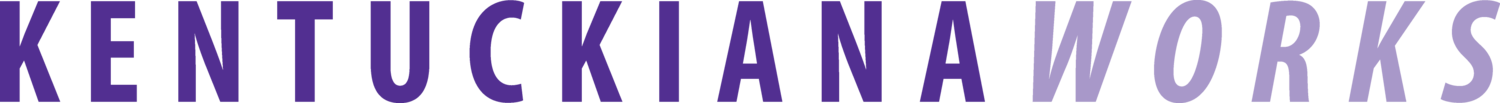

Within the Louisville metropolitan area, roughly one in 10 (11.7%) of young people age 16 to 24 who are not institutionalized are neither working nor in school. That amounts to just over 16,000 young adults. Youth disconnection is both serious and costly for young people and society itself. Young people facing disconnection miss out on opportunities to learn new skills, gain experience, and expand their social networks[1]. Disconnected youth are more likely to face persistent poverty and unemployment, engage in criminal behavior and substance abuse, and be incarcerated in their lifetimes than individuals that were not disconnected in their young adult years[2]. Disconnection costs tax payers billions of dollars in public support and lost tax revenues[3]. Failing to address the problem becomes a self-perpetuating cycle as the children of disconnected youth face similar outcomes as their parents[4].

It is important to understand where the Louisville area stands on the issue of disconnected youth, who is most likely to become disconnected, and highlight some of the targeted strategies that have worked to reduce the rate of disconnected youth in the metro area.

There is a significant increase in the proportion of disconnected youth as individuals become legal adults. Nineteen-year-olds are 8 times more likely to be disconnected than sixteen-year-olds. It is likely that the “Graduate Kentucky” law, which increased the age a student could drop-out of high school from 16-years-old to 18-years-old is having a positive impact on reducing the rate of disconnectedness for young adults age 16 to 17.

Broken down by demographic group, Louisville has a higher rate of youth disconnection among black and white racial groups. Only Hispanic youth in Louisville are less likely to be disconnected than Hispanic youth in our peer cities.

Family income is by far the strongest predictor of youth disconnection in Louisville. Over one-third (36.8%) of disconnected youth live below 100% of the federal poverty threshold.

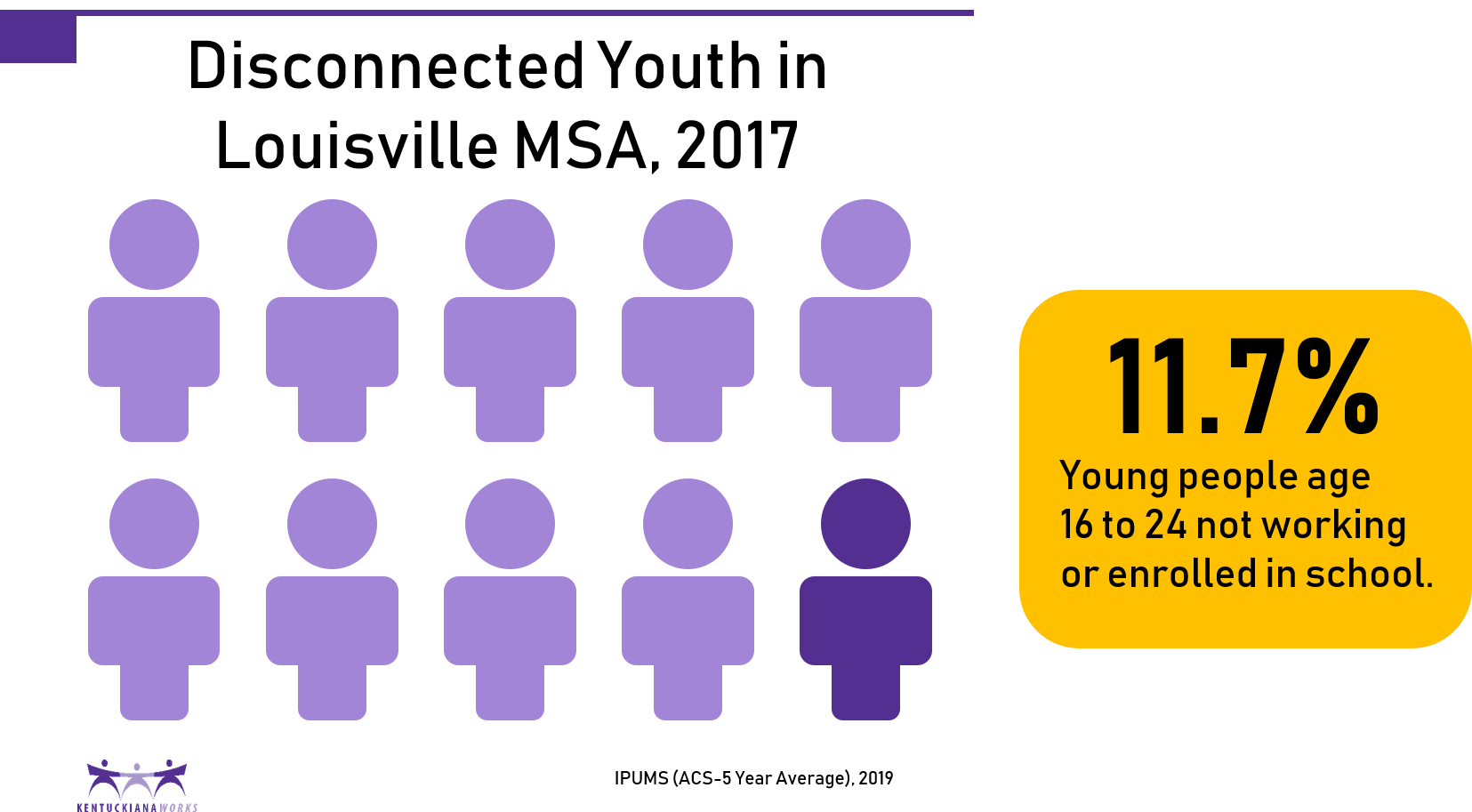

Teens in Louisville with either mothers or fathers residing in their household are less likely to be disconnected than teens whose parents are not living in the household. The presence of fathers in the home is particularly significant, reducing the likelihood of being disconnected for all demographic groups. For black males between 16 and 19, having their father in the household means they are 4-times less likely to become disconnected. For black females between 16 and 19, having their father in the household means they are 8-times less likely to become disconnected.

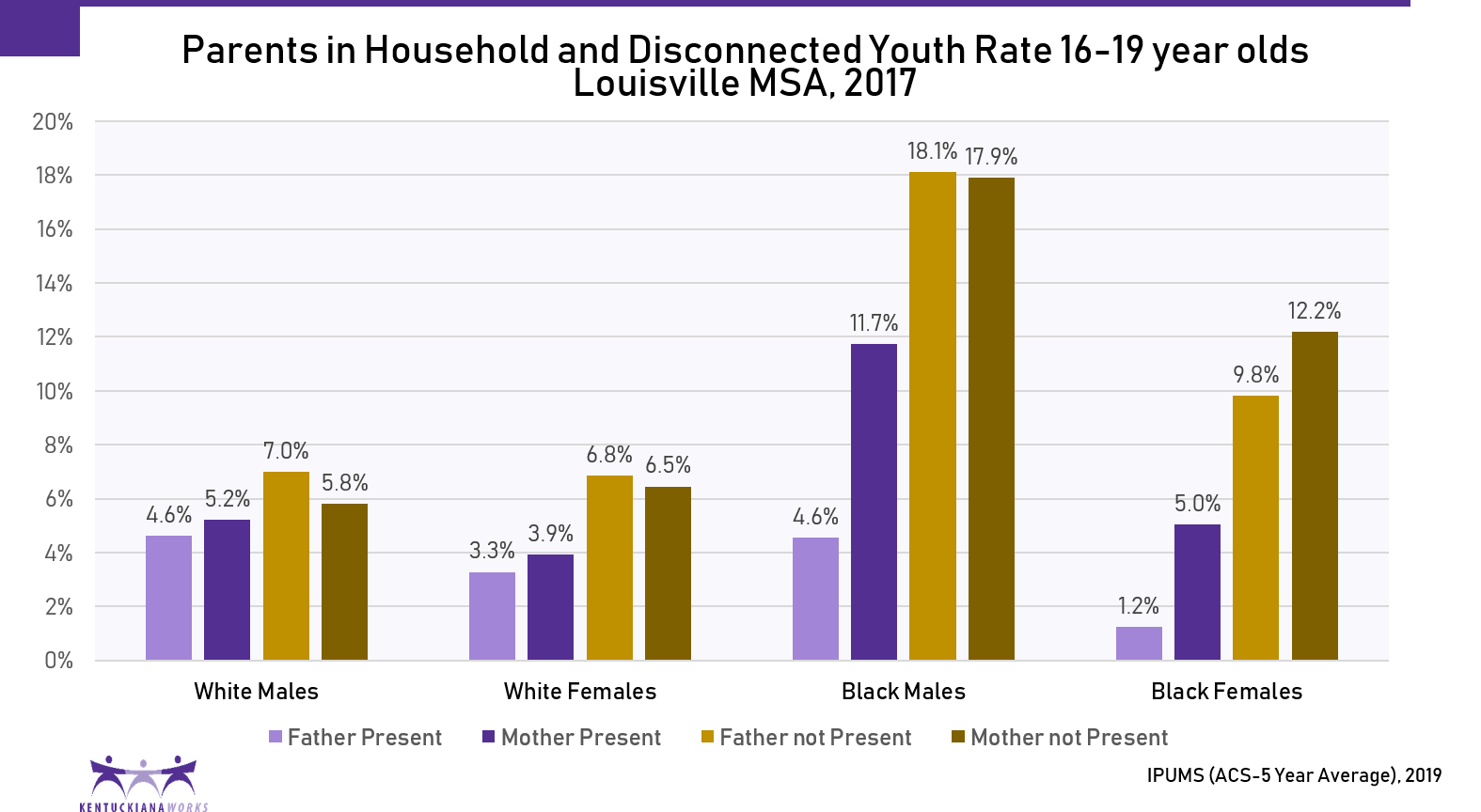

Educational attainment is also associated with the rate of disconnection among young adults. In Louisville, less than a quarter of young adults 20-24 with a high school degree or equivalency were disconnected, while 45.3% of young people without a high school degree were disconnected.

Having a disability greatly increases the likelihood of being a disconnected youth. Only 4.3% of Louisville’s youth have a reported disability. However, over a third (36.2%) of 16-24-year-olds with a disability are considered disconnected. As youth with disabilities in Louisville age out of the public education system, their likelihood of being disconnected doubles.

For women, having children greatly increases the likelihood they will become disconnected. Women with children are twice as likely to become disconnected than women without children.

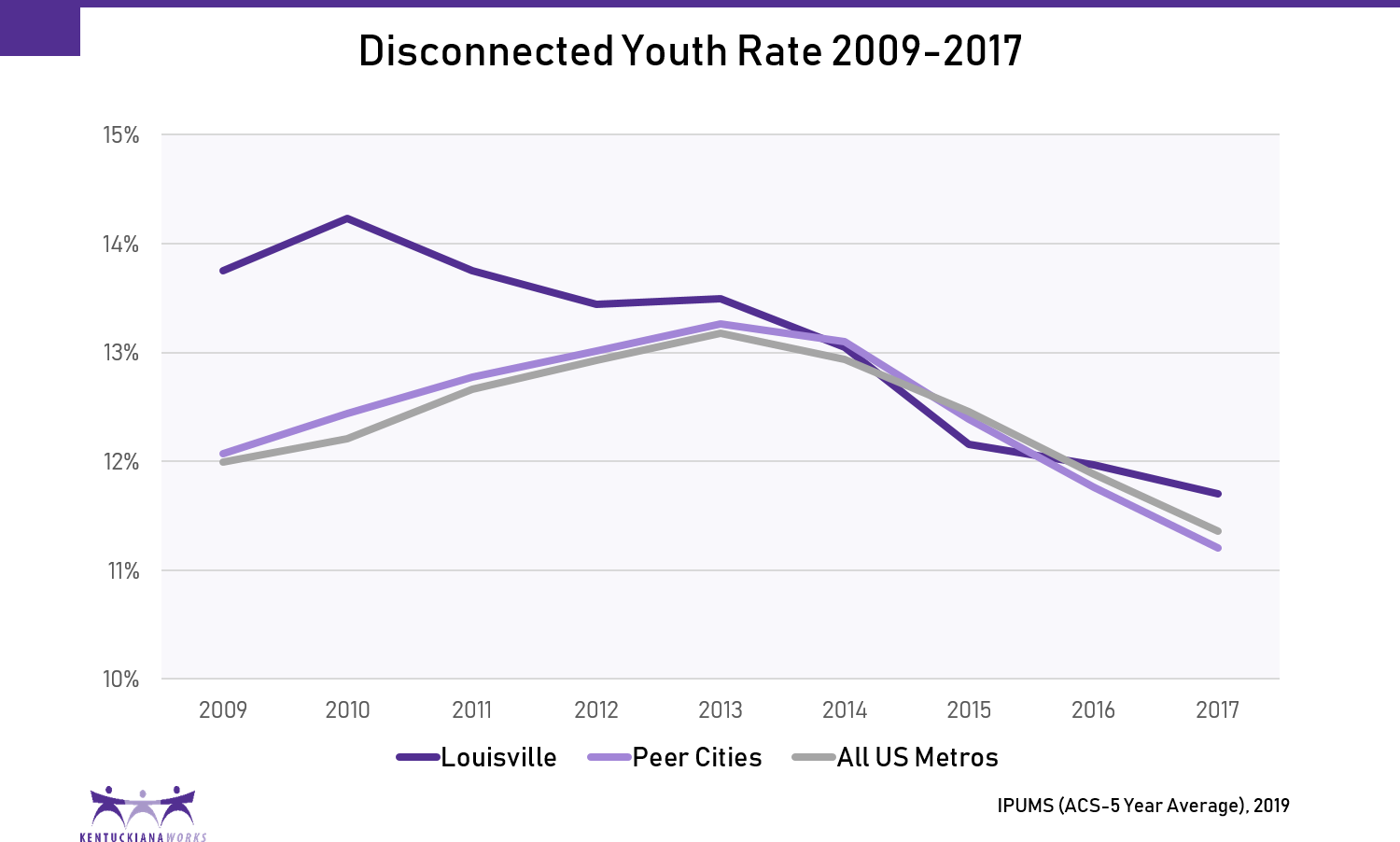

Since the end of the Great Recession, the number of disconnected youth has been trending downward both in Louisville, as well as nationally and in the peer cities. In Louisville, the rate of disconnection among youth has declined by 17% since 2009, although it still remains higher than the national average and the average of the peer cities.

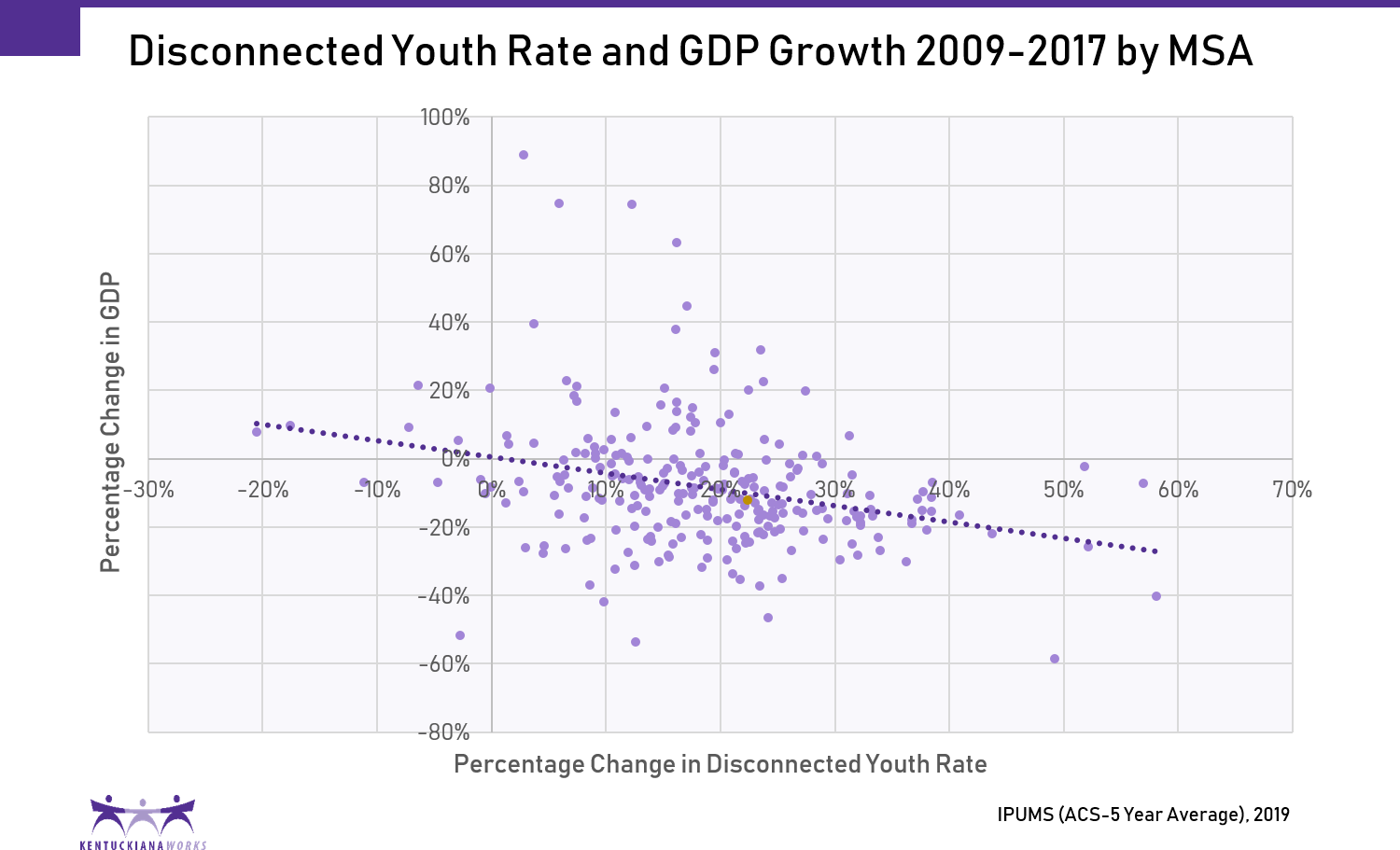

However, it would be unwise to suggest the reduction in the rate of disconnected youth is solely the result of economic growth. While an improving economy is helping to get some young workers into the labor market, there is a weak correlation between GDP growth and reduction in the rate of disconnected youth. Investments by the Louisville community to improve the areas of educational attainment, workforce connections, and wrap-around support for programs have likely been key in reducing the rate of disconnected youth [5].

Policies to reduce the number of disconnected youth should consider two approaches: re-engaging youth who have become disconnected as well as preventing disconnection in the first place.

Policy Intervention: Educational Attainment

Since education plays an important role in determining if a young adult becomes disconnected, policies should aim to increase the educational attainment of young people. Experiential learning models at the high school level like the Academies of Louisville keep young people engaged, which makes it more likely that young people will complete high school[6]. Quality after school programming like those supported through the BLOCS program help improve academic performance and soft skills[7]. Access to post-secondary education is made easier through programs like the KentuckianaWorks College Access Center and Evolve502. For young people who have dropped out of school, programs at the Kentucky Youth Career Center, Reimage, and YouthBuild provide an avenue to gain higher levels of education.

But there is still more that can be done. Research shows that access to high quality early childhood education can have long-term positive impacts on education and workforce outcomes[8]. But almost half of kindergartners in Jefferson County Public Schools are not ready to learn when they enter school[9]. Providing universal preschool would improve readiness to learn, academic performance, and school engagement, making it more likely that a young person will graduate high school and be transition ready[10].

Policy Intervention: Workforce Connections

Exposure to quality, in-demand jobs and different career pathways early in their education helps youth understand the array of job opportunities available, making it more likely a young person will stay connected[11]. The Academies of Louisville and the Area Technology Centers provide a real-world connection to local jobs and industries, and support meaningful engagement with the workforce. SummerWorks provides an opportunity for young people to gain work experience through a summer job, often times their first job. Programming through the Kentucky Youth Career Center and Reimage enable disconnected youth to gain work readiness training and job placement assistance. Project CASE provides career pathway exposure and job placement for individuals with disabilities.

But there is still more that can be done. Limited transportation options can prevent young people from obtaining and retaining employment, so improved public transportation would facilitate greater workforce connections. Indeed, research shows there is a strong association between the rate of disconnected youth and the average commute time for workers in a neighborhood[12]. Access to reliable, affordable transportation options helps to close the gap between neighborhoods and quality jobs and education centers.

Policy Intervention: Wrap-Around Support

There are many policies and programs in place to help reduce the rate of disconnection among young people in Louisville. However, coordination among all of these services is lacking, making it difficult for a young person to navigate the resources that are available. The newly announced United Community initiative aims to connect services across different organizations so that resources can be accessed more easily. Additionally, the Coalition Supporting Young Adults (CSYA), is an organization that attempts to connect service providers and identify gaps in coverage for Louisville’s youth.

Programming through the Kentucky Youth Career Center and Reimage include bus passes, a food pantry, professional clothes, and case managers so that young people have all of the resources they need to be successful. Evolve502 aims to not only provide young people with a promise scholarship to earn a free two-year degree, but also incorporates supportive services into their model. Programming that includes wrap-around services such as these rather than focusing solely on job or school placement increase the likelihood that a young person will stay connected and be successful. Such supportive policies are especially important for young people with disabilities who often require special accommodations and support to overcome employment barriers.

Conclusion

Louisville has made a lot of progress in pursuing policies and programs that have helped to reduce the rate of disconnection among young people. But this should not be taken for granted. The funding and partnerships needed to maintain these resources must continue to be protected. The city can continue to grow the policies and programs that will impact young people’s ability to engage with education and workforce systems.

References

[1] Adrienne L. Fernandes and Thomas Gabe, “Disconnected Youth: A Look at 16- to 24-Year Olds Who are Not Working or in School” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2015)

[2] Clive R. Belfield, Henry M. Levin, and Rachel Rosen, “The Economic Value of Opportunity Youth” (Washington: Civic Enterprises, 2012)

[3]Opportunity Nation. “Youth Disconnection.” (2019) https://opportunitynation.org/disconnected-youth/

[4] Measure of America. “One in Seven: Ranking Youth Disconnection in the 25 Largest Metro Areas” (2012)

[5] Fernandes-Alcantara, Adrienne L. “Vulnerable Youth: Background and Policies.” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2018)

[6] David Rapaport, “Experiential Learning: A Case Study Approach” (Cambridge: 2013)

[7] BLOCS: Building Louisville’s Out-of-School Time Coordinated System. “Data Report 2018”

[8] Jade M. Jenkins, et al. “Boosting School Readiness: Should Preschool Teachers Target Skills or the Whole Child?” (Economics of Education Review, 2018)

[9] Kentucky Department of Education. School Report Card, 2017-2018 School Year.

[10] Tamar Mendelson, et al. “Opportunity Youth: Insights and Opportunities for a Public Health Approach to Reengage Disconnected Teenagers and Young Adults” (Public Health Reports, 2018)

[11] National League of Cities Institute for Youth, Education, and Families, “Reengaging Disconnected Youth” (2016)

[12] Measure of America. “Making the Connection: Transportation and Youth Disconnection” (2019)